The Dream, One Hundred Years After Freud

An excerpt from the essay "Dreaming Outside of Ourselves" by James Hillman (UE 8 Philosophical Intimations)

How shall we regard (the dream) now, a hundred years after Freud’s extraordinary book?

First, let us review just what Freud’s accomplishment was in 1900. His Traumdeutung brilliantly solved the problem of the dream as it was then formulated.

During the nineteenth century, three dominating hypotheses held sway and conflicted with one another. The Romantic view regarded the dream as a personal message from the “beyond” with personal significance for the dreamer.

The Rationalists denied sense to dream contents altogether. Romantics and Rationalists agreed that the dream—because it was nonsensical garbage produced by the mind/ brain while resting (Rationalist) or it was poetic mystical inspiration from the deep soul or elsewhere (Romantic)—did not belong to the province of science.

The Materialist view, in contrast, favored scientific research, but only to prove the organic origin of the dream, its source in physiology. This research aimed to reduce dream events to body activities and sense stimuli.

Freud’s genius synthesized the three opposing views. By reasserting the ancient tradition that the dream has an immediate personal meaning for the dreamer, he absorbed the Romantic position. He also recognized the nonsense and irrationality of dream language, yet gave a rational account of the causality of this nonsense in what he called “the dream work.” Thus his view was not only Romantic but Rationalist as well. Then, by means of the sexual theory of the libido, he could integrate the Materialist position that there was an organic basis for the dream. He thus brought together these contrasting strands of the nineteenth century and wove them into a coherent theory of dreams.

A hundred years later, what do we want to hold onto of this “coherent theory of dreams”? Because of what has been so widely refuted and surpassed, we will no longer be captivated by Freud’s “science.” We will have to find new values in the dream other than revelations of infantile reminiscences and disguised sexuality. While holding onto the dream’s importance, we will have to revise why it is important, no longer because it offers intrasubjective information, all about me. And, we will hesitate to interpret the dream by lifting repression from it with the selfish, empowering aim of gaining territory and energy so as to consolidate and strengthen the Promethean “me.” Let’s not forget, Prometheus was a Titan whose human-centered focus offended the gods, cleaving us from them and disturbing the balance of the cosmos.

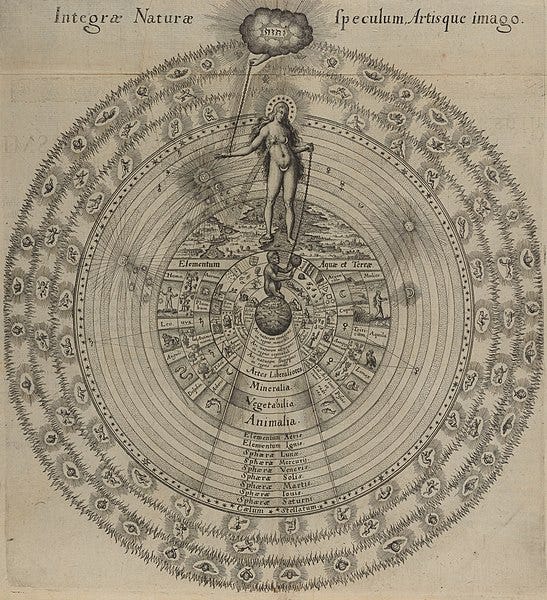

At this perilous point in the planet’s history, we will have to go further out than even the Romantics, by drawing on archaic ideas of dreaming as a source of imaginal information from a psyche that is not merely mine, attached to my brain and within my skull. If the psyche is more than subjective, but has a collective, objective, transpersonal, or archetypal aspect—which philosophical tradition calls the anima mundi—then the dream, too, must be referred beyond the person of the dreamer to the soul of the world.

This suggests that our dreams are dreamings of the “other.” This other is not merely the other parts of myself (“ my unconscious”) or the other as the repressed, forgotten, distorted, disguised. Rather, the dream brings in the fundamental other—the “not me” of the world and the specifics of how I am with it, in it. The world’s soul echoes and moves its imagination in my dream.

The dream still remains “mine.” It occurs in my part of the night. But as the night is not made by me, neither is the dream. In actuality, during the dreaming, I am in it, moving among its figures and scenes, held in its drama which I did not write. I am in it until the moment of awakening, when I reverse the facts and take possession of the night by saying, “I dreamt,” asserting that the dream is in me. Yet all night long I was in the dream.

Freud saw that the sickness of the other comes through the via regia (“royal road”) of the dream. In his day, that sickness used young city women in centers of patriarchal empire (Paris and Vienna) to demonstrate its symptoms. Today the symptoms are everywhere. The anima mundi is sick and the “other” cannot be contained within the consulting room. After one hundred years, illness permeates the planet itself.

I am suggesting that we meditate on dreams for a wider awareness of the cosmos that impinges upon us through the night window of the soul. To refer the dream to the anima mundi implies that the dream be welcomed for its information regarding the state of the soul of the world. The via regia would now lead away from a human-centered psychology and into a world-focused cosmology—psychology deconstructing itself as it dissolves into cosmology.

We would still be following Freud’s intentions and maintaining the deepest values of his thought because the unconscious would still be the concern of the work. However, the location of unconsciousness would now be out there rather than in us. We would still aim at lifting repression, though the content of the repressed would be different. For what is repressed today is the soul of the world, that the world of nature, of things, of technology and systems is not merely Cartesian dead matter, a barren objective res extensa (ie., material world), but also a res cogitans (ie., ensouled world)—layered with psychic potential once we shift our cosmology. That shift might end psychoanalysis as we now practice it. It would provide a fresh vision for another century of Freud, his investigative intellect, his radical spirit, his therapeutic concern for civilization, and his ideal of formulating a universally valid theory of psyche.

Excerpted from James Hillman, Philosophical Intimations, Uniform Edition 8

Available from Spring Publications