I’ll never forget the first time someone spit on me.

It was toward the end of an ayahuasca ceremony in the Amazon jungle about an hour away from Iquitos, Peru. I was sitting in front of the curandera who’d just guided me on a wild inner journey with a personalized playlist of beautifully sung icaros when she leaned in and whispered “manos.”

I offered her my hands, palms up, and heard an audible glug! as she took something in her mouth. She then blew a fine mist of cool liquid on my hands, the sharp, sweet smell of flowers and freshly turned earth rising to my nose. Next, she gently drew my head down and proceeded to blow another spray on my crown. I felt my head clear and heart open, which was so refreshing and enlivening after a few hours immersed in the dark, dank and sometimes scary journey with ayahuasca.

This wasn’t the first time I’d experienced the psychedelic power of scent while journeying with ayahuasca — limited mostly to burning Palo Santo and the occasional whiff of essential oil — but it ignited a fascination with the shamanic use of perfume that’s still with me almost a decade later.

The plant spirits in the Amazon love strong, sharp, sweet smells. Thus, one way to acquire protection against malevolent persons and their pathogenic projectiles is to acquire such a sweet smell oneself… Shamans achieve this state, and provide it for their patients, by putting substances with sharp sweet smells either on or inside the body.

— Stephan Beyer

Since time immemorial, spiritual practitioners the world over have utilized incense and perfumes in their rituals for healing, protection and divination. In the Amazon there are specialized shamanic practitioners called perfumeros, who create custom colognes that are used for cleansing, healing, spiritual protection and attracting love.

“Love and protection” are a dominant theme in the Amazonian shamanic traditions I’ve encountered. Whenever I’d ask a healer what a particular amulet, perfume or tapestry was for, they’d inevitably reply “amor y protection.” I’ve always loved the simplicity of this intention. I mean, what does anyway really need other than love and protection?

“The appeal of perfume is that it is at once ephemeral and empowering. It creates a shimmering invisible armor that lingers in a room long after its wearer has gone and infuses our imagination with a subtle power, hinting at a hidden identity.” — Mary Gaitskill

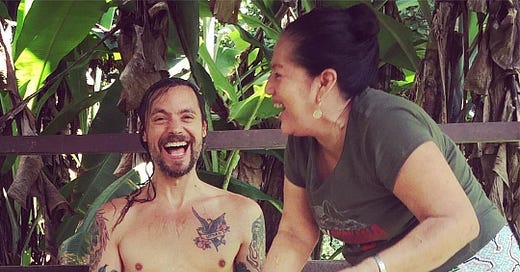

A perfume created with the intention to attract and cultivate love is called pusanga, and I later learned that Lila (the curandera who popped my shamanic perfume cherry) was known for her powerful love potions. I believe it. Lila radiated an earthy sensuality and sly humour. I enjoyed flirting with her and making her laugh, giving me a glimpse of her gold-capped teeth and playful spirit.

The best opportunity for this was when she was giving me a flower bath, pouring the plant-infused water over my head and down my shorts, eliciting a feigned cry of “Ai! Muy frio!” from me every time. The baño de flores is a supplementary shamanic practice and another one of the myriad ways that Amazonian curanderos utilize plants in their healing practice.

A usage that initially surprised me, but made sense once I thought about it, was how the healers would clean the maloka with gasoline (gasoline!) after every retreat and bar entry for a few days while it worked its magic. When I asked about this curious practice, I was reminded that gasoline is made from concentrated ancient plant matter which is highly refined, similar to perfume. So it makes sense that if you believe in the power of plants to spiritually cleanse a space, gasolina would be the most powerful perfuma para limpieza.

Another intriguing aspect of Amazonian shamanism is the widespread use of Agua de Florida, a cologne produced the Murray & Lanman company, based in New York City.

Murray & Lanman Florida Water was first introduced in 1808 as an alcohol-based essential oil concoction inspired by the Fountain of Youth, which according to lore existed in the Spanish colony of Florida — Juan Ponce de Leon’s first attempt at colonization in the United States. — https://substack.com/@carolineweaver

“Florida Water” was likely introduced to South America via the extractive rubber trade that began in the late 1800s. I can imagine the wives of rubber barons taking their perfumes to the Amazon in an attempt to bring a bit of civilized elegance to the jungle, the locals getting a whiff of it’s strong, sweet smell and immediately seeing its potential as a shamanic tool. It’s a great example of how cultural appropriation works both ways.

In the five years since my last time in the jungle, I’ve continued to used Agua de Florida in my own ritual practice (and as a hand sanitizer during COVID) and it never fails to remind me of my time in ceremony. Scent has the unique ability to evoke long ago memories, perhaps more than any other sense.

Just a couple of weeks ago my wife and I were visiting a friend in northern California for a short artist residency at the small museum she curates. The museum/art space holds the wildly eclectic collection of inventions and ephemera of the late eccentric renegade physicist and freethinker Larry Spring, who died in 2009 at the age of 94. The museum has a private residence attached to it where visiting artists can stay and among Larry’s vast collection is a case full of small bottles mounted over the toilet in the private bathroom.

Right away my eye was drawn to an art deco bottle in the shape of a woman’s torso emblazoned with a label identifying it as a perfume called Shocking by Schiaparelli. Of course I had to try it. I wrenched off the cap which had long ago cemented itself to the bottle. How exciting! It was like opening a crypt. The moment I dabbed a bit of it on my wrist I was transported back to the jungle. Somehow this vintage fragrance from the 1930s smelled exactly like Lilas famous pusanga and its scent transported me through time and space in the blink of an eye. I thought, “Oh my god, perfume is psychedelic.”

What is it about perfume that makes it such an unforgettable experience?

Certainly part of it is how we take it in. Smell is the most intimate (and invasive) sense. Unlike touch, taste or sight, smells get inside you. To taste something, we have to first choose to take it in our mouth and allow it to pass the gateways of lips and teeth. Smells, however, enter your olfactory orifices whether you like it or not. You have to smell something before you can choose to shut it out by plugging your nose, but eventually, you’ll have to open up to breathe.

I visualize perfume the way it’s depicted in old cartoons — a gaseous cloud uncorked from a genie bottle, floating through the air, into the nose and grabbing you by your limbic system. Some smells have the ability to pick you up and transport you down the stream of time.

In this way, scent is archetypal. Think about your associations with the smell of baby powder… fresh cut grass… incense… oranges. Our earliest memories are scent memories and smell is our earliest sense to develop. Just as babies recognize their mother by scent first and sight later, our ancient ancestors mapped the world with their noses first.

Studies have found that our sense of smell is connected to the deep emotional centres of our brain, and that our scent-memory is longer lasting than other forms of memory. Beyond the long-established use of essential oils and incense to affect our mood and sense of well-being, researchers are now exploring the ways that scent can help people who suffer from dementia, Alzheimer’s and other memory-related conditions remember by smelling objects and fragrances that evoke deep memories and emotions.

This seems to me yet another example of how modern science is finally catching up with what the Amazonian shamans figured out long ago — that plants have the power to transport us through time and space and that scent can radically shift our state of mind and heart. There’s almost nothing like a beautiful scent that carries warm and comforting associations to chase away the oppressive cloud of a dark mood.

“Smell is a potent wizard that transports you across thousands of miles and all the years you have lived.” – Helen Keller

The undeniable fact that scent plays a profound role in our spiritual and psychological evolution as humans makes it all the more troubling how it has been “problematized” in recent years. The proliferation of “scent-free zones” as an extension of the obsessive focus on enforcing “safe and inclusive” spaces has demonized the wearing of perfume. The irony that this kind of prejudicial exclusion goes directly against the ideal of inclusivity is so obviously hypocritical that I find it baffling.

This fatwa on fragrance not only makes our public spaces more sterile and soulless, it is oppressive to the human need for personal expression and autonomy. Even more troubling to me is how the fragrances that once attracted the good spirits and kept away the bad have gradually been made verboten. First they came for tobacco, then they came for incense and perfume — all of which have been used since time immemorial for both spiritual protection and worship. The widespread prohibition on fragrances leaves us lacking in both spiritual safeguarding and support.

Scent is one of the primary ways we interface with spirit. How else to distinguish the breath of God from that of the Devil? One is sweet, the other foul.

Thankfully, as this gradual constriction around scent has been taking hold of our society, there’s been a simultaneous increase of awareness of the spiritual power of fragrance thanks to the growing popularity among Westerners of non-Western traditions such as shamanism, yoga and Buddhism, Vodou, Candomblé, Santería and even Eastern Catholicism.

There is also a growing online and increasingly offline IRL community of perfume educators, collectors and appreciators. I’ve heard reports of young people getting together to share their recent perfume finds with each other and learning the intricate and image-rich language of perfumery. I hesitate to call this a “secular” use of fragrance because the community is so passionate and the way they describe perfume is indistinguishable from the language people use to describe their psychedelic or spiritual experiences.

Thanks to Jack Mason, host of a popular perfume and culture podcast, I’ve even been venturing outside the hippy-friendly world of essential oils and incense and exploring some mass market perfumes. (My current favourites are Terre D’Hermès, Yatagan by Caron, Encre Noire by Lalique and Lush’s Karma and Breath of God.)

Personally, I hope that people keep exploring the spiritual and soulful use of fragrance and resist the increasingly stifling rules and regulations of the cryptomatriarchy by boldly choosing to wear fragrances that reflect their identity and aspirations, thus reclaiming their free and unhindered access to the invisible spiritual realm of scent. Let’s call it dissenting against de-scenting.

Perfume is psychedelic — literally “soul revealing” — in that it both reveals the hidden essence of the plants it’s made from, and the artistic soul of the person who wears it.

Further reading:

Stephan Beyer, “Strong Sweet Smells” https://singingtotheplants.com/2007/12/strong-sweet-smells/

Ross Heaven, “Plant Spirit Shamanism: The Pusanga” https://rossheaven.livejournal.com/3422.html?

Caroline Weaver, The History of Florida Water

The Connections Between Smell, Memory, and Health

https://magazine.hms.harvard.edu/articles/connections-between-smell-memory-and-health

Mary Gaitskill, “The Power of Perfume” https://www.harpersbazaar.com/beauty/makeup/advice/a1037/power-of-perfume-1112/

Article on the olfactory cortex: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Olfactory_Cortex#:~:text=The%20Olfactory%20Cortex%20is%20the,lobe%20and%20the%20hippocampal%20formation

Luca Turin & Tania Sanchez, Perfumes: The A-Z Guide

https://www.amazon.ca/Perfumes-Z-Guide-Luca-Turin/dp/9949889677/