Watch/listen to this essay on my YouTube channel

There has been a lot of writing and videos made on the topic of narcissism over the past number of years, but I never see much attention given to the ancient story from which the personality trait derives its name.

There is also a trend of demonizing the narcissist, with many videos explaining the ways we can cut them off, shut them out, leave them and even torment them. I don’t see enough attempts to understand the inner life of the narcissist and to have compassion for what is, in reality, a tormented existence. This is the goal of depth psychology — to gain a deeper understanding of pathology so we can, with compassion, help the person (or help ourselves) find their way out of the underworld.

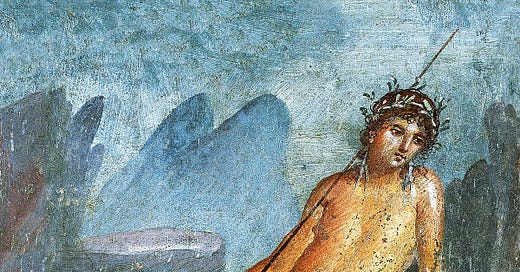

In my quest to gain a deeper understanding of this phenomenon I decided to follow the suggestion of James Hillman who, following his teacher Carl Jung’s advice, tells us to “stick with the image.” Because narcissism is one of the few (if only?) personality disorders named for a mythical character, surely the myth itself must contain some valuable insights that can help us understand it on a deeper level.

And if we understand it on a deep level, perhaps we can not only avoid the tragic fate of Narcissus ourselves, but also find some compassion for those afflicted with his curse. So with that as our goal, let’s leave behind the diagnostics and statistics of the psychiatric manuals and how-to’s of pop-psychology and return to this ancient tale to see what we can learn.

For this exploration, I’ve used the telling of the Narcissus myth from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which seems to be the most complete and detailed. It’s certainly the most poetic. The version I drew from was translated by Charles Martin and published in 2004.

Narcissus at sixteen seemed to be both

boy and man, and many boys and women

desired him; but in his yielding beauty

was such inflexibility and pride

that no young man or woman ever moved him.

Already we hear that Narcissus appears to be both “boy and man” at the same time. It may seem normal for us in this day and age that a youth of sixteen would be a kind of man-child hybrid, but it was perhaps an odd enough occurrence in the ancient world to warrant mentioning as the first thing we learn about Narcissus. In much of ancient Greece, a youth this age would have been inducted into temple ritual and apprenticed to a trade since about the age of seven.

We also learn that Narcissus is prideful, stubborn, aloof and emotionally distant. That he is still displaying these adolescent qualities in his young adulthood suggests that perhaps some crucial element was left out of his upbringing that would have initiated him into maturity.

In today’s world, largely due to the lack of functional rites of passage, we find many men who retain disagreeable adolescent qualities well into adulthood. Anyone who’s met a truly narcissistic personality has likely experienced the uneasy uncanny valley feeling that is evoked when encountering a grown adult who has the emotional maturity of an adolescent.

One day Narcissus happened to be roaming

the countryside when Echo* happened by,

and at the very sight of him grew hot;

she secretly pursued him through the woods,

her heat increasing as she overtook him,

as torches smeared with highly flammable

sulfur ignite themselves, brought near a flame.

*Echo is a nature spirit who was cursed by the goddess Juno to be “unable to keep still when someone spoke, or speak at all before another did … repeating just the last words of any speech she heard.”

Often she wanted to come on to him,

accost him with endearments, tender prayers—

but her nature won’t permit such forwardness:

advances are denied her, though she may

repeat, in her own voice, a sound she hears.

This passage about Echo suggests something about the kind of person who is attracted to the narcissistic personality, that perhaps someone who is disconnected from their own voice, and by extension unable to express their true self, is susceptible to enchantment by the glowing charm of the narcissist.

That day Narcissus was cut off from his companions,

and called out, “Anyone here?”

“Here!” answered Echo.

Narcissus searches all around, astounded:

cries out more loudly,

“Come!” His cry returns;

he turns around, but there’s no one approaching:

“Why do you run away from me?” he asks,

and the very same words are given back to him.

He halts, astounded by that other voice:

“Here let us come together,” he cries out,

and Echo gave her heart with her reply,

“Come! Together!” And leapt out of the woods,

eager to give her words a little help

by swiftly embracing the desired neck;

he flees, and fleeing, cries, “Hands off! No hugs!”

“I’ll die before you’ll have your way with me!”

In this exchange between Narcissus and Echo we get a sense of the narcissist’s refusal (or inability) to open to physical and emotional intimacy and their need to exert control over themselves and others. Both behaviours are defences against vulnerability. They’d rather die than allow someone to have their way with them.

Again we discover another important insight into the narcissist’s inner life. While they may appear invincible and heroically courageous on the outside, their grandiosity and confidence are usually masking deep insecurity, fear and fragility.

“You’ll have your way with me,” Echo replied.

Spurned, shamefaced, she slipped into the woods

and hid herself, living alone in caves

from that time on. And yet her love endured,

increased even, by feeding on her sorrow:

unsleeping grief wasted her sad body,

reducing her to dried out skin and bones,

then voice and bones only; her skeleton

turned, they say, into stone. Now, only voice

is left of her, on wooded mountainsides,

unseen by any, although heard by all;

for only the sound that lived in her lives on.

While this passage is more about Echo’s fate than Narcissus’, it describes through powerful imagery the effect that shame and unrequited love have on the soul, leaving one alone, wasted and dried out — a mere echo of one’s former self.

He’d trifled with her and so many others,

water nymphs, nymphs of the wooded mountains,

as well as a host of male admirers.

One of those spurned raised his hands to heaven:

“May he himself love as I have loved him,”

he said without obtaining his beloved,

and Nemesis assented to his prayer.

Narcissus’ trifling with Echo and his other admirers resonates with the emotional games that narcissists often play with people, drawing them close only to withdraw or push them away. When one trifles with another it shows a lack of respect for the other, hinting at an inflated sense of self, what the Greeks called hubris. In ancient Greece, someone was guilty of hubris when they had the arrogance to assume the status of a god, or otherwise go against the gods — the downfall of many heroes of myth.

Nemesis is the Greek goddess that brings retribution for the offence of hubris. She is a personification of the force of nature that maintains balance in the cosmos and keeps mortals in their right place. Psychologically, we can understand Nemesis as the enemy of the inflated ego. And as many of us have experienced, anyone who challenges the narcissist’s ego will quickly become their nemesis.

There was a clear pool of reflecting water

unfrequented by shepherds with their flocks

or grazing mountain goats; no bird or beast,

not even a fallen twig stirred its surface;

its presence nourished greenery around it,

and the surrounding trees would keep it cool.Worn out and overheated from the chase,

here comes the boy, attracted to this pool

as to its setting, and reclines beside it.

And as he strives to satisfy one thirst,

another is born; drinking, he’s overcome

by the beauty of the image that he sees;

he falls in love with an immaterial hope,

a shadow that he wrongly takes for substance.

The details in this passage tell us something important about the affliction of narcissism. Notice that the pool is completely isolated. There are no shepherds, no beasts or birds, nothing to disturb its reflecting surface. It speaks to the fragile nature of the narcissist's false self-image. As the passage states, there’s no substance to it. It’s merely a shadow. It’s fragile because it’s not based on reality. To preserve the illusion the narcissist must always stay cool and keep anyone from getting too close.

Transfixed, suspended like a figure carved

from marble, he looks down at his own face;

stretched out on the ground, stares into his own eyes

and sees a pair of stars worthy of Bacchus,

a head of hair that might adorn Apollo;

those beardless cheeks, that neck of ivory,

the decorative beauty of his face,

and the blushing snow of his complexion;

he admires all that he’s admired for,

for it is he that he himself desires,

all unaware; he praises and is praised,

seeks and is the one that he is seeking;

kindles the flame and is consumed by it.

Narcissus sees in his reflected image the qualities of the gods. It’s an idealized self-image, more like a marble carving than a human face. There’s a deep insight here if we look (or listen) deeply enough. What is it that Narcissus desires? He sees in his reflection an image of perfection, and what is god if not an image of perfect wholeness — what Jung called the imago dei — projected outwards?

When this god-image is projected onto one’s self-image (ego), it forms a perpetual feedback loop that keeps the person from developing their human qualities. If I’m perfect and whole, what more is there to do? And just like a jealous monotheistic god, the narcissistic ego needs constant affirmation and adoration.

If we follow another of James Hillman’s rules of thumb and “follow the symptom”, the story suggests that what the narcissist truly desires is god. From this we can speculate that perhaps the antidote to narcissism is an awakening to the spiritual realm and the cultivation of a religious attitude that recognizes that I am not perfect and there are forces in the universe much greater than me.

“The main interest of my work is not concerned with the treatment of neurosis but rather with the approach to the numinous.”

— C.G. Jung

Jung himself asserted that “the main interest of my work is not concerned with the treatment of neurosis but rather with the approach to the numinous…the fact is that the approach to the numinous is the real therapy, and in as much as you attain to the numinous experiences you are released from the curse of pathology.”

Numinous is a term that Jung borrowed from philosopher and psychoanalyst Otto Rank to describe the indescribable experience of a spiritual power, entity or reality that evokes what Rank called mysterium tremendum — a sense of something mysterious, overwhelming, and daunting which elicits from us a sense of diminution, humility, submission, and creatureliness.

It was this key idea of Jung’s — that the cure for pathology was theology — that inspired the “letting go and letting God” aspect of the Alcoholics Anonymous 12 Steps. Interestingly there is a strong correlation between Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) and alcoholism, so perhaps there’s a corresponding treatment approach that could also help the narcissist recover?

If the root of narcissism is hubris, an inflated self-image, then perhaps it needs to be brought down to earth, its bubble burst by a humbling encounter with the numinous. As Jung commented, “the experience of the Self is always a defeat for the ego.” For Jung, the Self was itself “numinous, a sort of god.”

Considering the numinous encounter as an antidote for narcissism leaves us with the question of how to initiate this kind of ego-shattering experience. It is likely to be catastrophic for the narcissistic ego, as the tragic end of the Narcissus myth so powerfully illustrates. The old meaning of ‘catastrophe’ is a turning downward, or overturning. And that might be just what the narcissistic personality needs — to overturn the tyrannical ego in order to have an experience of the deeper self. Jung’s student Marie-Louise Von Franz writes, “The actual processes of individuation — the conscious coming-to-terms with one's own inner center or Self — generally begins with a wounding of the personality.”

But we must be careful. There are numerous reports of how psychotic breaks can be triggered by the ingestion of psychedelics, intensive meditation retreats, and other spiritual practices. What these kinds of experiences share is that they offer the potential for a sudden encounter with the numinous mystery. In some cases, such as with smoking DMT, an ego death experience is often the primary aim. But without a self-image that is related to the greater self or greater mystery — what Jung called the ego-Self axis — egocide easily has the potential to lead to suicide.

Jungian psychologist Donald Sandner wrote about the potential of transformative ritual to break the narcissistic ego out of its closed feedback loop through a death-rebirth experience:

“Death and rebirth are the mythological symbol for a psychological event: loss of conscious control, and submission to an influx of symbolic material from the unconscious. Personality growth is usually thought of as cumulative, a gradual expansion through time as ego consciousness gains experience and wisdom. But often it turns out to be only a pursuit of illusory ideals. Then there is cessation of growth, stultifying depression, or, more ominously, severe illness. At that point no halfway measures will do; a thoroughgoing transformation is necessary for the individual’s survival. Like the sun, the ego must prepare itself for a plunge into the darkness of the unconscious underworld, there to experience rejuvenation.”

Donald Sandner, Navaho Symbols of Healing: A Jungian Exploration of Ritual, Image, and Medicine, 1979

Having explored the nature of narcissism and its potential antidote, let us re-enter our story at the point in which Narcissus’ self-love turns into self-torment, considering it both as a cautionary tale of what happens when the narcissist’s self-image is disturbed too suddenly and too completely, and as a way to better understand and have compassion for the narcissist’s accursed affliction.

How many times, in vain, he leans to kiss

the pool’s deceptive surface or to plunge

his arms into the water, keen to clasp

the neck he glimpses but cannot embrace;

and ignorant of what it is he looks at,

he burns for what he sees there all the same,

aroused by the illusion that deceives him.Why even try to stay this passing fancy?

Child, what you seek is nowhere to be found,

your beloved is lost when you avert your eyes:

that image of an image, without substance,

arrives with you and with you it remains,

and it will leave when you leave—if you can!For neither his hunger nor his need for rest

can draw him off; prone on the shaded grass,

his insatiate stare fixed on that false shape,

he perishes by his own eyes.…

“My grief is draining me, my end is near;

soon I will be extinguished in my prime.

This death is no grave matter, for it brings

an end to sorrow. Of course, I would have been delighted

if my beloved could have lived on,

but now in death we two will merge as one.”Maddened by grief, he spoke and then turned back

to his image in the water, which his tears

had troubled; when he saw it darkly wavering,

he cried out, “Stay! Where are you going? O cruel,

to desert your lover! Touch may be forbidden,

but looking isn’t: then let me look at you

and feed my wretched frenzy on your image.”And while he mourned, he lifted up his tunic

and with hard palms, he beat on his bare breast

until his skin took on a rosy color,

as parti-colored apples blanch and blush,

or clustered grapes, that sometimes will assume

a tinge of purple in their unripened state;

the water clears; he sees what he has done

and can bear no more; just as the golden wax

melts when it’s warmed, or as the morning’s frost

retreats before the early sun’s scant heat,

so he dissolves, wasted by his passion,

slowly consumed by fires deep within.Now is no more the blushing white complexion,

the manly strength and all that pleased the eye,

the figure that was once quite dear to Echo.

And seeing this, she mourned, although still mindful

of her angry pain; as often as the wretched

boy cried, “Alas!” she answered with “Alas!”And when he struck his torso with his fists,

Echo responded with the same tattoo.

His last words were directed to the pool:

Alas, dear boy, whom I have vainly cherished!”

Those words returned to him again, and when

he cried “Farewell!” “Farewell!” cried Echo back.His weary head sank to the grass; death closed

those eyes transfixed once by their master’s beauty,

but on the ferry ride across the Styx,

his gaze into its current did not waver.The water nymphs, his sisters, cut their locks

in mourning for him, and the wood nymphs, too,

and Echo echoed all their lamentations;

but after they’d arranged his funeral,

gotten the logs, the bier, the brandished torches,

the boy’s remains were nowhere to be found;

instead, a flower, whose white petals fit

closely around a saffron-colored center.

Brian James is an archetypal coach and depth counsellor. He hosts the popular podcast Howl in the Wilderness, which features interviews with renegade artists, musicians, psychologists, and spiritual teachers. Learn more at http://brianjames.ca