Does A.I. Dream of Electric Sheep?

What do Blade Runner, Philip K. Dick, James Hillman and Archetypal Psychology tell us about what reliance on Artificial Intelligence does to the soul?

As a musician, graphic artist and someone who writes and talks a lot about creativity, psychology and the soul, I get asked more and more these days about what I think of A.I.

The stock answer I’ve been giving is that “every time we outsource our writing or creativity to A.I., we give away a piece of our soul.”

Whenever I give this reply, I’m usually challenged by artists or writers who defend their use of A.I. by stating that “it’s just another tool” and I then feel the need to explain why I don’t agree that it’s “just another tool.”

Since I’ve been thinking more deeply about the implications of A.I. for the human soul — thanks to recent conversations on my podcast (like this one with depth psychologist Glen Slater), books I’ve been reading (Erik Davis’ TechGnosis, Meghan O’Gieblyn’s God, Human, Animal, Machine), and movies I’ve been watching (Blade Runner) — I thought it’d be a good time to expand on my stock answer and flesh out some of the ideas that have been rattling around my all-too-human brain.

My main argument against utilizing A.I. to make the creative process more “efficient” is that when we use it to leap over the gap that lies between the seed of an idea and its fruition, we’re missing out on the creative toil that actually grows our soul.

For this to make any sense to someone who hasn’t been immersed in the work of James Hillman as I have been for a number of years, we first have to come to some mutual understanding of what it means to have soul in the first place. Notice that I said have soul, not have a soul. This is an important distinction in understanding Hillman’s poetic view of the soul, one which deftly skirts around any religious and philosophical debate about the ontological reality of the soul (Hillman did love tap dancing.)

What we’re talking about instead is the metaphorical soul that we refer to when we speak of depth of feeling, meaningfulness, and the wisdom and dignity that is accrued through love, loss and other formative experiences.

It’s what the poet John Keats was talking about when he wrote,

“Call the world, if you please, "the Vale of Soul Making". Then you will find out the use of the world....Do you not see how necessary a world of pains and troubles is to school an intelligence and make it a soul? A place where the heart must feel and suffer in a thousand diverse ways....”

I came to this view of soul through Hillman, who loved Keats’ idea of soul-making so much that he made it the cornerstone of his archetypal psychology.

At the heart of this poetic understanding of soul-making is a challenge to the Christian assumption that we are all born with a soul that is either lost or saved through Christ. Instead, it suggests that soul is made through feeling and suffering your way through life.

With this notion of soul in place, I might further refine my stock answer concerning A.I.: “When we outsource the creative struggle to A.I., we miss out on an opportunity for soul-making.”

So why do you care so much? Is A.I. really that big a threat?

I care deeply about maintaining soulfulness in my life and soulfulness in the world, so it pains me when I see people eagerly embracing A.I. as a way to make their creative process more efficient (soul time is slower, soul asks for patience). Sometimes I feel like I’m the only one who thinks it might be contributing to the loss of soul that is already causing what an early guest on my podcast, John Vervaeke, has named “the meaning crisis.”

Hillman wrote in his magnum opus Re-Visioning Psychology:

“However intangible and indefinable it is, soul carries highest importance in hierarchies of human values, frequently being identified with the principle of life and even of divinity.

In another attempt upon the idea of soul I suggested that the word refers to that unknown component which makes meaning possible, turns events into experiences, is communicated in love, and has a religious concern.

These four qualifications I had already put forth some years ago. I had begun to use the term freely, usually interchangeably with psyche (from Greek) and anima (from Latin). Now I am adding three necessary modifications.

First, soul refers to the deepening of events into experiences; second, the significance soul makes possible, whether in love or in religious concern, derives from its special relation with death. And third, by soul I mean the imaginative possibility in our natures, the experiencing through reflective speculation, dream, image, and fantasy—that mode which recognizes all realities as primarily symbolic or metaphorical.”

Following Hillman, I am saying that A.I. can never produce soulful writing or images because it isn’t confined to a body and therefore can’t die — it doesn’t have the “special relation with death” that would produce the sense of significance that deepens events into experience.

A.I. also seems to have no capacity for imagining — another function of soul. As far as I know, it always needs to be prompted by a human with an idea — unless A.I. daydreams and spontaneously produces words and images and I just haven’t heard about it — and it can only work with material that already exists via human creativity.

So, not only does using A.I. to bypass the creative process rob us of valuable soul-making opportunities, it doesn’t add soul to the world with what it creates.

Sci-fi author and psychedelic mystic Philip K. Dick poses the question “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” in the title of the 1968 novel that was the inspiration for the film Blade Runner. The book’s protagonist Rick Deckard, an android bounty hunter who is forced to wrestle with the moral implications of his job when he starts to empathize with the more sophisticated, human-like androids he’s tasked with “retiring”, asks himself at one point, “Do androids have souls?”

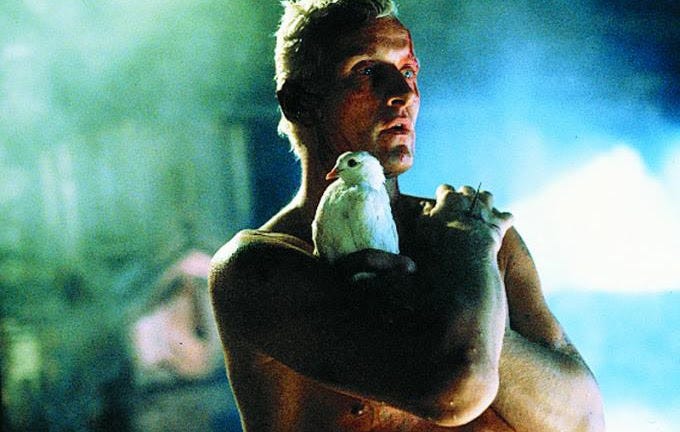

While the book is less explicit in answering this question, the film, particularly in the final scenes with the Blake-quoting, philosophically-oriented android Roy Baty (spelled “Batty” in the film), suggests that they do. Although, since androids are “made, not born” the question of how they can have souls is left to the viewer to ponder.

Ironically, when we meet Deckard he’s a man clearly suffering from soul loss. He’s a downtrodden, lonely nihilist who’s pretty much given up on life — until he falls in love with an android. The non-human androids that he’s meant to destroy, particularly his love interest Rachael and the enigmatic Roy Baty, actually help him recover soul.

If we think about soul, following Keats and Hillman, as something that is itself “made,” then we can see how over the course of the film Baty has been involved in soul-making to the extent that when he dies and the dove symbolically flies toward the heavens, he has become ensouled.

His famous final soliloquy resonates with Hillman’s ideas about soul-making.

“I've seen things you people wouldn't believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.”

Baty reveals an appreciation for life that lends significance to the events he witnesses that turn them into experiences. They have deep meaning for him, and he grieves his demise because he wants to experience more.

In the film he seeks out his maker in order to compel him to “repair what he’s made” and extend his life beyond the 4-year expiration date of the android body. This is the special relationship to death that Hillman ascribes to soul. Because androids are made of biological materials, they decay and eventually perish. Soul needs a body that dies in order to grow.

In Re-Visioning Psychology James Hillman draws distinctions between soul and spirit as metaphoric modes of being and experiencing:

“The spiritual point of view always posits itself as superior, and operates particularly well in a fantasy of transcendence among ultimates and absolutes.

Images of the soul show first of all more feminine connotations. Psyché, in the Greek language, besides being soul, denoted a night moth or butterfly and a particularly beautiful girl in the legend of Eros and Psyche.”

Our discussion … of the anima as a personified feminine idea continues this line of thinking. There we saw many of her attributes and effects, particularly the relationship of psyche with dream, fantasy, and image. This relationship has also been put mythologically as the soul's connection with the night world, the realm of the dead, and the moon. We still catch our soul's most essential nature in death experiences, in dreams of the night, and in the images of lunacy.

The world of spirit is different indeed. Its images blaze with light, there is fire, wind, sperm. Spirit is fast, and it quickens what it touches. Its direction is vertical and ascending; it is arrow straight, knife sharp, powder dry, and phallic. It is masculine, the active principle, making forms, order, and clear distinctions. Although there are many spirits, and many kinds of spirit, more and more the notion of spirit has come to be carried by the Apollonian archetype, the sublimations of higher and abstract disciplines, the intellectual mind, refinements, and purifications.”

James Cameron’s 1991 film Terminator 2 offers a great illustration of these distinctions. In it, the older model of Terminator played by Arnold Schwarzenegger is a machine embodied by living flesh, whereas the newer model, the T-1000, is made of shapeshifting, mercurial molten metal.

Over the course of the film, we witness the Terminator becoming more ensouled, feeling such empathy for the humans he was sent to destroy that he, in the end, sacrifices himself so that they can live. The T-1000 however remains a cold, heartless killing machine.

Androids, because they have a biological, mortal body modelled after our own, have potential for soul-making. A.I., on the other hand, fits more into Hillman’s idea of spirit. Soul is embodied, feminine, slow, instinctual, immanent. Spirit is disembodied, masculine, quicksilver, intellectual, transcendent.

Is it any wonder then that the greatest evangelists for A.I. are intellectually-oriented men who, in their heroic Apollonian fantasies, seek to transcend the limitations of the human body and the physical laws of the Earth body? In their quest for transcendence they resemble modern day Techno-Gnostics who yearn for higher realms of existence, omnipotence and freedom from death.

In my recent conversation with Douglas Rushkoff on A.I. and psychedelics, I pointed out that Elon Musk is a regular user of Ketamine, a drug known for its anesthetizing and dissociative properties. Ketamine is the perfect drug for a man who would rather be a disembodied consciousness. Is he really the kind of person we want to entrust the future of humanity to?

It is this lack of appreciation for the messy, emotional, often painful embodied life that makes me most wary of A.I. and its proponents. Those of us who are more soul-centered accept, and even embrace, the limitations that our embodied existence places on us, because we intuit that it’s the limitations and the endings that make life meaningful. And if life has no meaning, what would be the point of preserving it?

The Vale is a compilation of writing, research and rumination by Brian James.

Brian James is a depth counsellor, archetypal coach and host of the Howl in the Wilderness podcast, living in the wilds of Vancouver Island, Canada with his wife, astrologer Debra Stapleton and rescue mutt Suki. Learn more at brianjames.ca